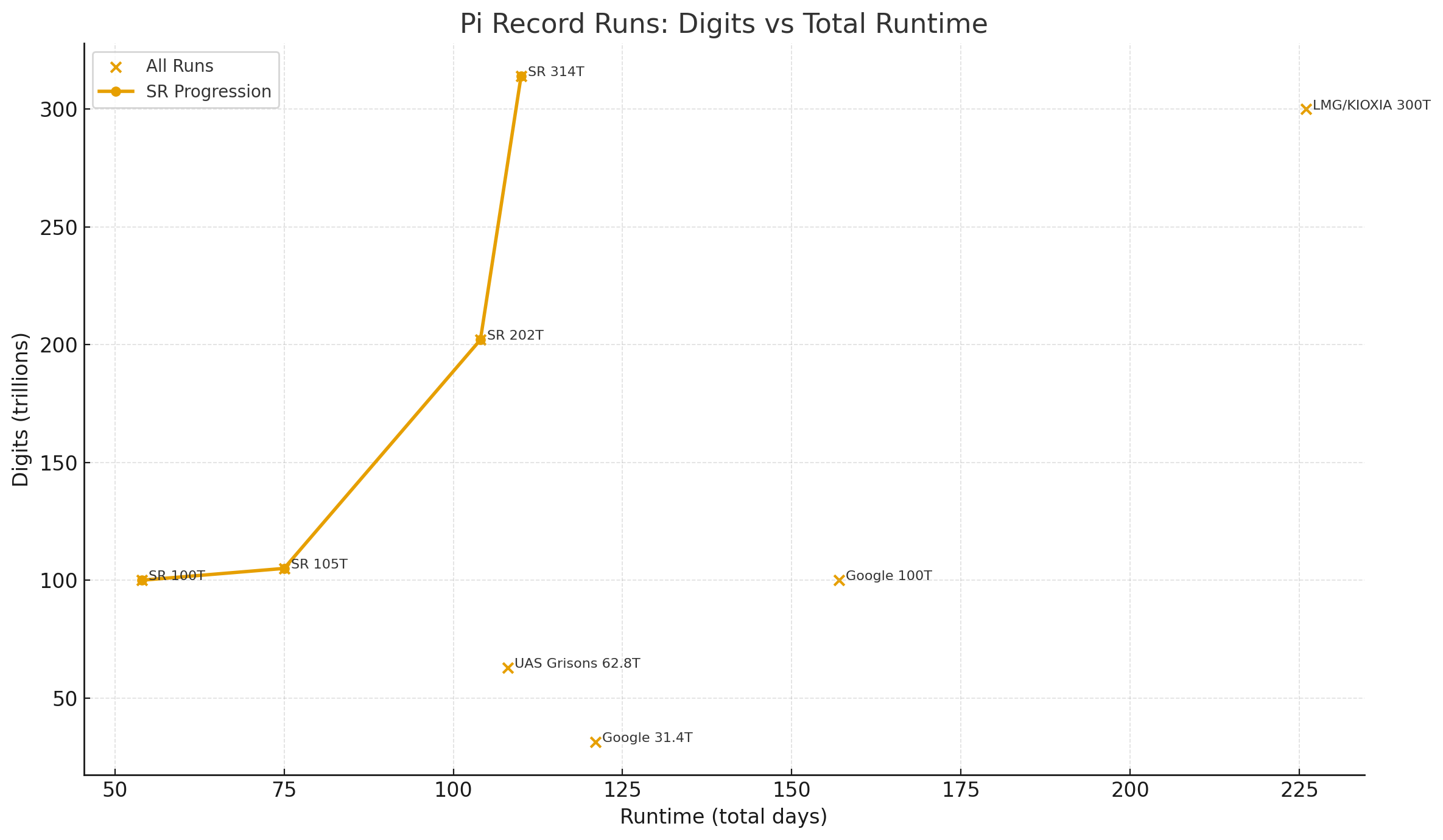

StorageReview has reclaimed a popular computational crown with a new pi record solve to 314 trillion digits. The modern π race has gone from cloud experiments to full-blown infrastructure flex. In 2022, Google Cloud pushed π to 100 trillion digits, running y-cruncher across a massive fleet of cloud instances and chewing through tens of petabytes of I/O in the process. That mark stood as the headline number for “how far is possible” with traditional infrastructure.

The action then shifted into the lab. In early 2024, we upgraded our record to 105 trillion digits on a system supported by nearly a petabyte of Solidigm QLC SSDs. This achievement set a new benchmark for scale and demonstrated how efficiently a single on-premises machine could operate. A few months later, we did it again, this time reaching 202 trillion digits. This validated that high-density flash and careful tuning could outperform hyperscale infrastructure for this specific, demanding workload.

Of course, records invite challengers. Linus Media Group and KIOXIA grabbed the crown with a 300 trillion-digit run, powered by a large Weka shared-storage cluster with 2PB of flash. That effort showed what storage-heavy traditional infrastructure could do, albeit with a rack of hardware, a large power bill, and cooling complexities. We couldn’t idly stand by and let that record stand!

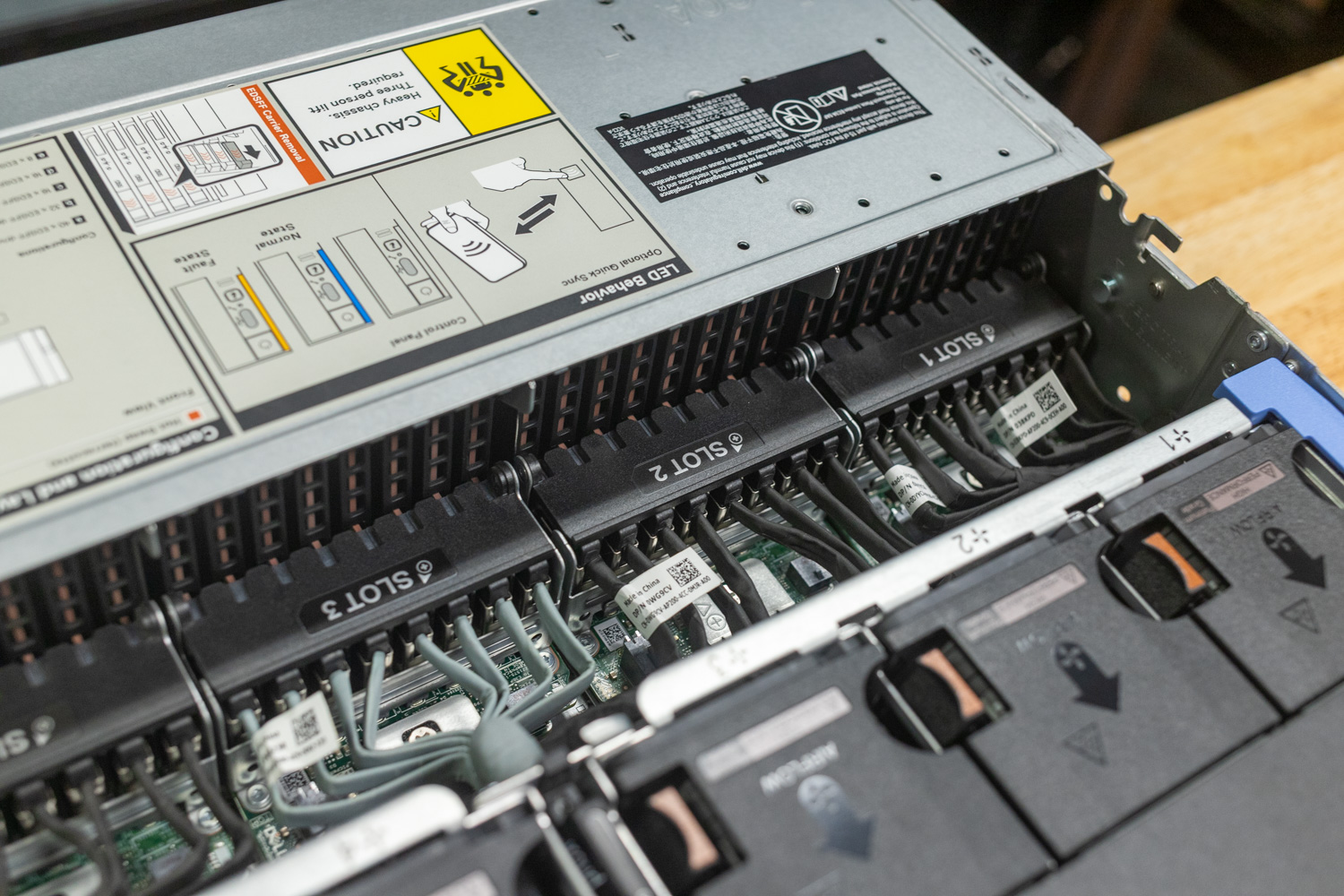

StorageReview has now pushed π to 314 trillion digits, using a single 2U Dell PowerEdge R7725 server equipped with dual AMD EPYC 192-Core CPUs and forty 61.44TB Micron 6550 Ion SSDs. With the system build and tuning taking place in July, we kicked off our run on July 31, 2025. As luck would have it, our pi run wrapped during our second day of SC25, fitting for a new HPC record.

Scaling y-cruncher to 314 Trillion Digits

Once you cross into the hundreds of trillions of digits, y-cruncher behaves less like a traditional benchmark and more like a long-haul infrastructure stress test. The application itself is straightforward, but the way it interacts with hardware at this scale becomes the determining factor. Everything comes down to how well the system can keep thousands of multi-precision operations moving without stalling the CPUs or overwhelming the storage layer. The storage layer, specifically, is where this record was actually won. We deployed 40 Micron 6550 Ion Gen5 NVMe SSDs, 34 of which were allocated to y-cruncher. This SSD pool delivered about 2.1 petabytes, giving y-cruncher enough space to perform the 314T run. The remaining 6 SSDs were used to build a software RAID10 volume, which we used to record the 314T digits of pi.

Design changes between the 16th- and 17th-generation Dell PowerEdge servers also contributed to improving the performance of our most recent 314T record run. In our previous 202T record, we leveraged the 24-bay Dell PowerEdge R760, which used a PCIe switch on the drive backplane, trading drive density for performance. On the 17th-generation Dell PowerEdge servers, such as the Intel-based R770 or AMD-based R7725, the backplanes reverted to direct-connect-only, with 2 or 4 PCIe lanes per bay. In the PowerEdge R7725 with its 40-bay Gen5 E3.S backplane, each SSD gets 2 PCIe lanes. While that may seem like a performance hit, the platform is still capable of reaching up to 280GB/s read and write when all 40 bays are hit simultaneously.

Using the internal y-cruncher storage benchmark, we recorded the storage performance of each platform in the configuration used for each run. Across each workload, we saw storage performance increases ranging from 72% to 383%, with balanced read and write metrics.

| Metric | 202T System (old record) | 314T System (new record) | Percent Difference (314T vs 202T) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequential Write | 47.0 GiB/s | 107 GiB/s | +127.7% |

| Sequential Read | 56.7 GiB/s | 127 GiB/s | +124.0% |

| Threshold Strided Write | 62.2 GiB/s | 107 GiB/s | +72.0% |

| Threshold Strided Read | 20.9 GiB/s | 101 GiB/s | +383.3% |

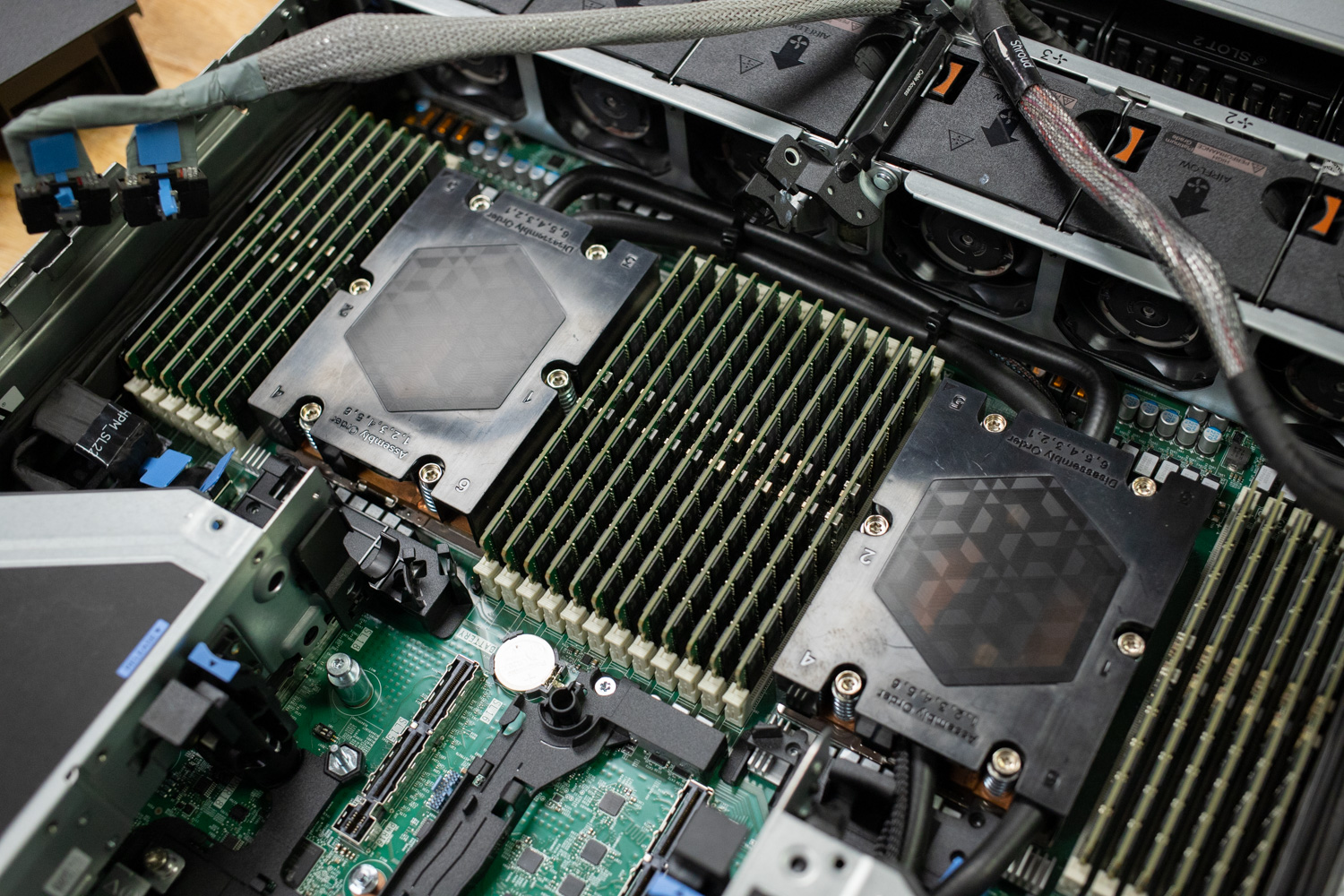

The Dell PowerEdge R7725 isn’t just a storage box; it also offers significant compute potential as a dual-socket AMD Turin platform. We leveraged 192-core AMD EPYC 9965 CPUs, totaling 384 cores. We also replaced the stock air-cooled heatsinks with liquid-cooled CoolIT SP5 cold plates, which were cooled by a CoolIT AHx10 Liquid-to-Air CDU. This combination kept the CPUs in higher sustained clock speeds, chassis fans operating at around 30% PWM, and our average system power consumption hovering around 1,600W.

On the software side, the platform ran Ubuntu 24.04.2 LTS Server instead of Windows Server as in past runs. This maximized system stability and delivered significant gains in workload performance. We performed numerous test iterations before committing to kicking off our run, including reserving 4 out of 384 cores for background system operations. The result wasn’t just beating the existing pi record; we obliterated it across numerous metrics. Nothing comes close to our run in terms of performance, power consumption, and most impressively, reliability. We are also the only large-scale pi world-record run without a second of downtime. From start to finish, the run never had to be resumed.

Record-Setting Power Efficiency

The approach StorageReview has taken for each of our pi record runs has been to reduce complexity and run the benchmark using as little power as necessary. The previous 300T record, which leveraged a distributed storage cluster and a high-speed network, came at the cost of larger power and cooling requirements. We took a different path, focusing on storage density to use a single 2U server for both swap and output storage. This played a significant role in reducing our overall power and cooling footprint. Our Dell PowerEdge R7725 consumed just 4,304.662 kWh over the course of the 314T run, which works out to just 13.70 kWh per trillion digits. This makes it one of the most energy-efficient large-scale pi computations. When comparing the two approaches, the difference becomes immediately apparent, as highlighted in the table below.

| Run | Total kWh | Cost @ $0.12/kWh | Cost @ $0.20/kWh |

|---|---|---|---|

| 300T Weka Cluster Run | 33,600 kWh (est.) | $4,032 | $6,720 |

| 314T Single-Server Run | 4,304.662 kWh | $517 | $861 |

It is important to note that during the calculation, our 314T run leveraged SSDs in a JBOD configuration without data resiliency. Power consumption and overall system performance were the factors that led to that decision, but it also sparked a discussion about designing the storage solution around the workload. Every workload is different, and some that can be restarted with minimal impact on production may not require the same level of fault tolerance. In our case, we focused on protecting the data output with traditional software RAID.

110 Days Total Runtime

Despite computing more digits than any run before it, the wall-clock time was significantly lower than the previous record, which required roughly 225 days to complete (175 compute days excluding downtime). The uninterrupted 110-day window is the result of a stable OS, a minimized background load, a balanced NUMA topology, and a scratch array engineered for the pattern y-cruncher generates at this scale.

Technical Highlights

- Total Digits Calculated: 314,000,000,000,000

- Hardware Used: Dell PowerEdge R7725 with 2x AMD EPYC 9965 CPUs, 1.5TB DDR5 DRAM, 40x Micron 61.44TB 6550 Ion

- Software and Algorithms: y-cruncher v0.8.6.9545, Chudnovsky

- SSD Wear per SMART: 7.3PB written per Drive or 249.11PB across the 34 SSDs used for swap

- Logical Largest Checkpoint: 850,538,385,064,992 (774 TiB)

- Logical Peak Disk Usage: 1,605,960,520,636,440 (1.43 PiB)

- Logical Disk Bytes Read: 148,356,635,606,263,504 (132 PiB)

- Logical Disk Bytes Written: 126,658,805,195,776,600 (112 PiB)

- Start Date: Thu Jul 31 17:16:41 2025

- End Date: Tue Nov 18 05:57:08 2025

- pi: 8793223.144 seconds, 101.773 Days

- Total Computation Time: 9274878.580 seconds

- Start-to-End Wall Time: 9463226.454 seconds

Closing Thoughts

For decades, extreme pi runs were a way to show off whatever counted as “big iron” at the time. Early records leaned on high-performance desktops and externally attached storage, then moved towards local enterprise equipment. More recently, the race moved into the cloud, where jobs like Google’s 100 trillion digit run proved that you could brute force your way to a record with enough instances and enough I/O. Then we saw large shared storage clusters step in, trading simplicity for raw parallelism and a tremendous power and cooling bill.

Our approach has gone in the opposite direction. Over multiple record runs, we have treated y-cruncher as a serious HPC workload, not a one-off stunt. The 105T and 202T solutions helped us identify the real bottlenecks, size and tune scratch storage, keep CPUs fed without thrashing the I/O layer, and harden a system so a months-long job actually finishes. The 314T run is the result of that experience. It is not just a bigger number. It is a more mature design.

The metrics reaffirm that story. We pushed past 300 trillion digits on a single 2U Dell PowerEdge R7725 with 40 Micron 6550 Ion SSDs and dual 192-core AMD EPYC CPUs, kept the system online for 110 straight days, and never had to resume from any failure. Storage throughput more than doubled compared to our 202T platform, yet the server averaged about 1,600W and consumed 4,305 kWh in total. That works out to 13.70 kWh per trillion digits, which is a fraction of the estimated energy used by the previous 300T cluster: fewer nodes, less complexity, less energy, more work done.

That is why this record matters beyond bragging rights: if one commercial 2U server can sustain a y-cruncher run of this size, with that level of reliability and efficiency, the same design patterns map directly to production science. Long-running climate models, physics simulations, genomics pipelines, and AI training jobs all live or die on the same fundamentals: balanced I/O, predictable thermals, stable firmware, and an architecture that can stay upright for months at a time. This platform has now proven it can do precisely that under conditions that leave no room for error.

Yes, StorageReview has reclaimed the pi crown with 314 trillion digits. More importantly, we have set the bar for what “good” means in large-scale numerical computing on real hardware. If someone wants to take the record, we would like to see them take the whole thing: more digits, less power, shorter wall time, and the same zero-downtime reliability. Until then, this is the benchmark for efficiency.

Amazon

Amazon